We are numb to numbers. In the aftermath of a tragedy, it is the fate of the individual not the scale of suffering that elicits compassion and mobilizes us into action.

![]() If I look at the mass, I will never act. If I look at the one, I will. ~ Mother Teresa

If I look at the mass, I will never act. If I look at the one, I will. ~ Mother Teresa

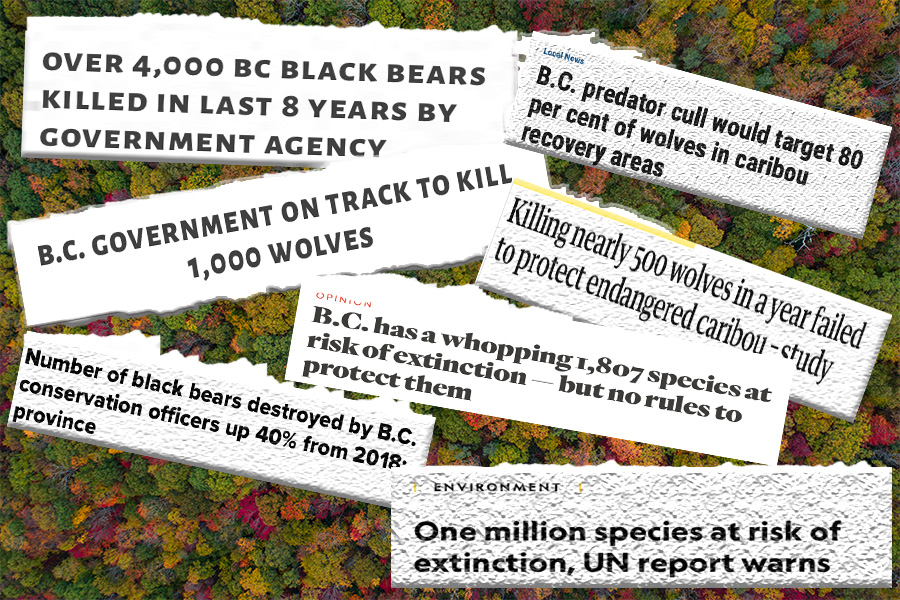

O ur natural world aches; its wounds fester. Environmental disasters have become not only more common but unprecedented in scale. Biodiversity is rapidly vanishing. We hear about it; we read about it. On May 6th, 2019, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) issued a report stating that “one million animal and plant species are threatened with extinction, many within decades, more than ever before in human history.” World Wildlife Fund (WWF) keeps updating its Living Planet Report that shows ever more staggering statistics about the vanishing natural world. In 2018, WWF reported a 60% decline in birds, amphibians, mammals, fish and reptiles since 1970. In 2020, WWF Canada announced that species that are at risk of global extinction have seen their Canadian populations decline by an average of 42% over the past 50 years. British Columbia alone has more than 2,000 species of animals and plants facing extinction, more than any other province or territory in Canada. In the same province, since 2015, more than 1000 wolves have been killed under the guise of caribou conservation, and the Conservation Officer Service (COS) has killed almost 5000 black bears since 2011.

Are you numb already by this litany of numbers? Has it made your eyes wander in search of some relief? If so, you are not alone. Global reports and regional studies make headlines that quickly fade into oblivion. The quantified scale of a disaster shock in its enormity and yet, surprisingly, hardly ever spurs sustained collective action.

In contrast, a single photograph or a story about an individual animal can move the public. Takaya, a lone wolf of Discovery Island, provides an example that epitomizes this phenomenon. One day, Takaya swam across the bay and ended up in Victoria, B.C. Fearing that he might be killed, British Columbians galvanized support for his relocation back to the wild. Instantly, the social media were inundated with the latest information about Takaya as well as pleas for his relocation back into the wild. The efforts succeeded, and Takaya was released to Southern Vancouver Island. Although tragically, the celebrated wolf was killed by a hunter two months later, the outpouring of emotions and the scale of the public response show how the power of a story about one animal can galvanize the public.

Psychic Numbing

Why does that happen? Why would the story of a single wolf mobilize some of the same people who remain indifferent or oblivious to the tragic fate befalling countless packs of wolves? Human psychology provides a partial answer. Decades-long research by Paul Slovic, a psychology professor at the University of Oregon, shows how the mental trait of psychic numbing dilutes the extent of our compassion.

Psychic numbing refers to the way humans process numerical information. It explains how, paradoxically, compassion decreases as the number of those who need our help increases. There is a survival logic to it. The human brain evolved to quickly recognize an immediate threat — a snake in the grass, a predator in the bush — and thus we favour speed and emotional reaction over reason. Speed is the domain of the instinctual system that translates the external world into easily accessible mental images. We can empathize with an individual’s tragedy because we are able to imagine an individual. A mental image of a unique sentient being is easier to generate and relate to than an image of 1000 wolves.

By definition, each individual possesses singular characteristics. In contrast, the quantification of large-scale tragedies merges countless cases of individual suffering into an abstraction that prevents emotional connection. What does the face of 500 wolves look like? How exactly do they suffer? It is hard, if not impossible, to imagine. Not Takaya, though. Even if we’ve seen only photos or heard about his fate, we can imagine the wolf endowed with features that made him unique. In fact, the majority of people never saw or met Takaya, but he touched their hearts and captured their imagination. A single Takaya has an advantage over numerous nameless wolves. He evokes our compassion because the traits he possessed — individuality, uniqueness, and irreplaceability — renders it possible for him to be loved, fought for, and now sorely missed. Whom, though, do you miss when you miss 500 wolves? A large number of killed animals obliterates our connection to the tragedy. The extent of lives lost speaks to the rational mind, but, at the same time, the abstract aggregate cannot reach the heart.

Indeed, as the leading brain scientist, Antonio Demasio, argues, it is largely through emotions that we make sense of reality. Emotions tell us what is right and what is wrong, and what we should care about. They drive us to respond to the sight of suffering, an image of anguish, and to blood staining the forest. Or to a mother bear taking her last breath as her orphaned cubs look on. This is who we are. Emotions make us respond to words such as “Takaya”, “freed” or “killed”, but they also prevent us from reacting to other words such as “occurrence” or “abundances”. They make us feel the death of one while numbing us to the anguish of many.

With a touch of irony, the American writer Annie Dillard illustrates the barriers of our affective system: “There are 1,198,500,000 people alive now in China. To get a feel for what this means, simply take yourself — in all your singularity, importance, complexity, and love — and multiply by 1,198,500,000. See? Nothing to it”. Of course, nothing is more misleading than saying that there is “Nothing to it”. Once we dispense with irony, the only word left to say is “impossible”. This is the only true answer to the task of emotionally grasping multitudes. And we know that. After all, we describe large-scale disasters as “unimaginable”, “incomprehensible,” or “unspeakable”, and so we concede that their ramifications extend beyond the limits of our comprehension and compassion.

The Quantification of Conservation Science

And yet, although individual stories have the potential to generate a more lasting public response than statistical descriptions or data-driven research findings, the ecological orthodoxy fails to embrace them. The fate of an individual animal gets dismissed by conservationists as deflecting attention from more existential concerns. That is understandable since conservation science’s foremost goal is to protect the diversity of all life forms and ensure that wild animals thrive in their natural habitats. From this standpoint, the survival of biodiversity eclipses the survival of any individual animal. And yet, counter-intuitively, the key to ensuring the well-being of multitudes might lie in activating our evolutionarily-wired preference for the individual.

The conservation field has not yet learnt this lesson. In its effort to study and manage wildlife populations, the scientific community dismissed the emotive power of an individual. Beauty, anguish, and suffering have been purged from the pages of scientific journals. Like a romantic naturalist who, older now, has turned into a detached professional researcher, conservation science traded the immediacy of emotions for the cold abstraction of empirical data.

Three factors help to explain this state of affairs. Firstly, the conservation field strives to obtain recognition and respectability commensurate with these of other areas of knowledge. As a result, it has immersed itself in numbers and statistical projections that have always been a domain of economics, mathematic or physics. Conservation scientists dutifully report how wildlife populations are increasing or decreasing, which are endangered and which are not. The field has even adopted vocabulary devoid of emotional appeal to better approximate scientific dispassion. It studies wildlife species through population models and estimates wildlife “abundance” or “occurrence”. Researchers talk about “healthy” black bear and wolf populations, and about hunting ‘quotas’ as if they were commodities. This is what we learn about wildlife when research findings reach the media.

Of course, if this is what many fields of science demand, this is what those who want to succeed in them provide. Here, again, the image of an impressionistic naturalist turned statistician becomes salient. Since turning passion into a respectable profession might require severing emotional linkages to nature, self-reinforcing factors come into play. Conservation science demands objectification and quantification. Hopeful researchers meet this demand, which, in turn, strengthens objectification and quantification trends already present in conservation science.

Finally, funding considerations also privilege numbers. By following this principle, conservation science not only establishes itself in the mainstream of academia but also makes its findings more persuasive to funding institutions. Both conservation organizations and government officials need a well-supported rationale to justify releasing funds or supporting a conservation initiative. Numbers, statistics, charts, and graphs have the allure of objectivity that is conducive to creating such a rationale.

A Failure to Embrace Emotions and Individual Stories

And yet, in terms of protecting biodiversity, the emulation of hard sciences has turned out to be a Faustian bargain. While attaining recognition and respectability, the wildlife conservation field has attenuated its link to potentially the most influential ally – ordinary people. The tendency of conservation science to resort to abstraction and quantification emerges thus as a tactical success but a strategic error. Psychic numbing has desensitized the public, and since, in democratic societies, citizens are conduits to political power, such numbing indirectly erodes the societal salience of ecological concerns. However, without having sufficient salience in the eyes of the voters, issues related to wildlife and biodiversity cannot count for much support.

This is the dilemma facing conservation scientists and wildlife organizations. People might not have strong opinions about esoteric economic theories or advanced chemical processes, but they have passionate views about the fate of individual animals. And, again, in democratic countries, public opinion matters. The extent of societal support for conservation projects or wildlife management actions can influence government policies and help release funding. Such support becomes, however, harder to generate if an effective emotional appeal does not accompany the urgency of numbers.

Downplaying the role of emotions dooms thus wildlife conservation to reside on the periphery of social concerns. The message of endless research studies, drowned in numbers, fails to capture the human heart. Indeed, how can one imagine, visualize, and relate to “biological diversity”? How can one feel an affinity with “a species”? One cannot. Only individual pain and struggle can move us, but these powerful realities are repackaged into dispassionate generalizations and numerical abstractions.

Overcoming Psychic Numbing

What to do then? Paul Slovic argues that we need “sensitive communicators to present information in a way that touches emotions and makes things imaginable.” A story of an individual can foster empathy and galvanize collective action. As Slovic states, “dramatic stories of individuals or photographs give us a window of opportunity where we’re suddenly awake and not numbed, and we want to do something.” Here lies the power of the emotional appeal. We, humans, make sense of reality through storytelling because, as Jean-Paul Sartre said, “a man is always a teller of tales, he lives surrounded by his stories and the stories of others.” A gripping story of a single life unfolds more compellingly and vividly than do statistics about the fate of countless lives. This is why great literature pulls us in and holds us captive, even if its overarching thematic canvas is war or revolution.

Most importantly, our compassion for an individual can help, if wisely harnessed, address challenges that numbers and statistics point to. Emotions and numbers do not need to be antithetical to each other. Both parts of the equation can work to advance the same goals. Again, the story of Takaya proves it. The wolf captured the imagination of people around the world. Artists have tried to preserve his memory. Cheryl Alexander, a photographer who documented Takaya’s life, created a Facebook page to commemorate him and carry on his legacy. But this is not only about Takaya. Alexander and others use the tragic story of the lone wolf to bring more attention to the plight of wolves in British Columbia. In the aftermath of Takaya’s death, wildlife advocates started a petition calling for a moratorium on wolf hunting and expose “a lack of scientific rigour on the part of the BC government [that] has led to citizen culls of wolves across the province.” The petition has already received almost 71,000 signatures. Takaya is gone, but one can hope that his story will save other wolves.

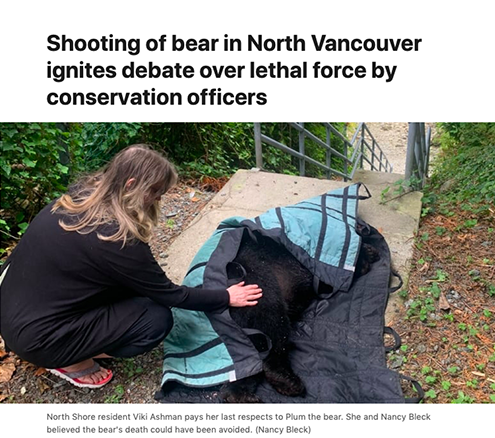

Saving countless wild animals might also be the legacy of two black bears, Huckleberry and Plum, killed by conservation officers in North Vancouver in the summer of 2020. The killings shocked the community, attracted media attention, and enlarged the ranks of those fighting for compassionate co-existence with black bears. Huckleberry and Plum also accelerated long-overdue changes to conservation policies at the municipal level. And it was precisely the individualization of these two bears, including naming them, that made the difference. As the North Shore Black Bear Society states on its Facebook page, “we never could have anticipated that naming Huckleberry and Plum and sharing their stories would bring so much attention to our Society and the plight of bears living in British Columbia.”

The fact that the North Shore Black Bear Society could not have predicted the effect of individualizing two bears shows that even those who empathize deeply with animals might fail to recognize the power of the individual. These dedicated people need to be praised and encouraged to have faith in their own beliefs. What moves them also moves the public. One can only hope that such success stories will motivate other wildlife organizations to use emotionally resonant stories as part of their efforts to mobilize public support.

There are signs that mainstream conservation science is beginning to acknowledge the role of emotions. For instance, scientists from the University of Victoria, B.C. used artificial intelligence tools to create grizzly bear face recognition software. As pointed out by the lead author Melanie Clapham, one of the advantages of the software is that “Learning about individual animals and their life stories can have really positive effects on public engagement and really help with conservation efforts.”

The purported “irrationality” of human emotions needs not to be derided nor bemoaned for its numbness to numbers. The human capacity for compassion is an unstoppable force. Once unleashed, it can transcend its singular focus and bring aid to those we know only through desensitizing numbers. Emotions do count, and compassion is an unalienable part of who we are. We must learn how to harness it, how to sustain it, and how to channel it into saving wildlife species and natural habitats.

The article originally published on Jan 6, 2021