Image Credit: Reno Sommerhalder

In the name of progress, we have built the world based on lies that codified the distorted vision of nature. Our anthropocentric worldview turned the wonder of the living world into an object of fear and hatred. No winners, only losers, emerged from the transformation.

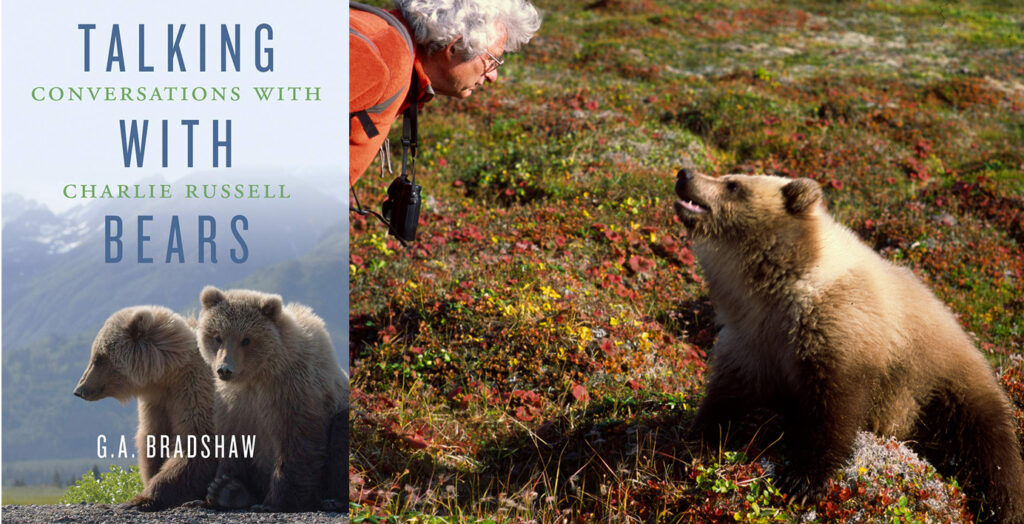

At times, one gets engrossed in a book because its topic is fascinating or unique. Sometimes, an author’s literary art renders an even less revelatory content irresistible. Finally, on a rare occasion, a story and an author’s way of telling this story conjoin to create a reading experience that etches itself in the heart and mind. Talking with Bears: Conversations with Charlie Russell is one of those books. We need to be grateful, almost relieved, for this to have happened because the beauty of Charlie Russell’s life deserves to be depicted in a beautiful and original way. Gay A. Bradshaw does exactly that.

The collaboration between Bradshaw and Russell might seem so unlikely that, had it been conceived of as fiction, one would dismiss it as improbable. And yet this “odd couple” – the double Ph.D. researcher and the immensely intelligent and perceptive, but largely self-taught, man – creates a remarkable book. From the first page’s poetic image of “the quiet growl of a snowmelt river” to the last chapter’s discussion of quantum physics, we know that we have stepped into the rich vein of artistic and intellectual treasures. However, we also realize that the book demands immersion and contemplative reflection from the reader. These are prerequisites when approaching Talking with Bears because the book’s merit lies in its holistic message as well as in its intriguing and enthralling details. Again, it is a fortunate merging of form and content. After all, one of the main lessons Charlie Russell tried to teach us is that paying attention to nature is a precondition to knowing the truth. In his case, of course, it also meant physically surviving.

Image Credit: Ryan Peruniak

Photo courtesy of Gay Bradshaw

While reading Talking with Bears, I recalled a passage from the book Serious Noticing written by the preeminent literary critic, James Wood. As Wood writes, “to notice is to rescue; to save life from itself.” This occurs because, in noticing details – in rescuing them from oblivion – we come closest to seeing the secular religion of nature. It is then that we embrace, in Walter Benjamin’s words, “the natural prayer of the soul: attentiveness.” Charlie Russell achieved this when coexisting with Bears in the natural world surrounding them. He seems to have lived the words of Adorno in Negative Dialectics: “if the thought really yielded to the object, if its attention were on the object, not on its category, the objects would start talking under the lingering eye.” In Adorno’s view and in contrast to Hegel’s dialectic, instrumental knowledge can never yield “the ‘pure voice’ of the Object.” Thus, to see the truth and its beauty, we must look at the natural world with new eyes: a tree must become the tree, and a bear must become the bear. Charlie Russell lived these words, and these words live on the pages of Gay Bradshaw’s book.

Thanks to Talking with Bears, we vicariously experience the splendour and harshness of an iconoclastic life. The book takes us on the hypnotic journey through the physical and spiritual landscape we hide so deeply from ourselves as though it never existed. Indeed, it is both the wild landscape where Charlie’s Bears roamed and the landscape inside us that have shrunken as our dominion over the natural world has grown. As we read, we realize how broken our world has become, and, inescapably, we sense that the word “broken” refers to its literal meaning, “fragmented into pieces,” as well as the metaphorical one, “despairing.”

Artist: Supneet Kaur

What Charlie and, through him, Bradshaw accomplish is to shatter the façade of a fulfilling life. In the name of progress, we have built the world based on lies that codified the distorted vision of nature. Our anthropocentric worldview turned the wonder of the living world into an object of fear and hatred. No winners, only losers, emerged from the transformation. Following the path of least resistance and misguided by the belief in our superiority, we shredded the natural world into pieces of isolated abstractions. And we have paid the price for it. To fit the world we have created, our brains have “evolved” to be able to perceive merely fragments of the delicate assemblage of life. But, of course, fragments lead only to a fragmentary life. Now uprooted – our primordial linkage to the intricate tapestry of life severed – we are trapped in constricting silos of self-imposed loneliness. Self-isolated from the world’s richness, we seek an ever-elusive fulfillment in transient trivialities while feeding our impoverished souls with the bland nourishment of consumerism and commodified nature.

Charlie Russell freed himself from this box and “walk[ed] unarmed in the terrain of the soul, in the space of stillness from which all life springs.” It is on this path that Gay Bradshaw takes us. As we follow Charlie’s steps, we explore the lushness of nature known to few and the lives of Grizzly Bears known to even fewer. It isn’t a sentimental journey, though. Yes, we can listen to Bears’ voices, feel their warmth, their kindness, but we also hear them weep and roar in pain. For Charlie had no illusions; he wore no rose-coloured glasses over his piercing eyes. If man mistreats a bear, he says, “a transformation into rage, fear and despair” is likely to result. Sadly, this will occur despite the Grizzly Bears’ peaceful nature, for even “the mighty grizzly is not always able to withstand humanity’s convulsive violence.” On a larger scale, Bradshaw argues,“ such departures from the Grizzly’s historic, restrained nature are symptoms of psychological trauma.” Indeed, in this and other aspects of the book, Charlie’s first-hand accounts are greatly aided by Bradshaw’s insights from her own groundbreaking research on post-traumatic stress disorder in non-human animals. Again, as always, it is the truth, the unvarnished truth, that Charlie and Bradshaw are after. And the truth also means violence, trauma, death. Ironically, these are Bears who suffer, not people as sensationalized accounts of exceedingly rare human injuries would lead us to believe.

Image Credit: Jeff and Sue Turner

Photo courtesy of Gay Bradshaw

But there is more to this story, a different side. The book is replete with accounts of moments of oneness, harmony, wonder, kinship, and love. Love, Charlie’s favourite word. And understanding. Here is the man who “never wanted to know about bears…only wanted to understand them.” Here are the Grizzly Bears that, despite the history of abuse by humans, showed “the capacity to heal past wounds” and “are still open and willing to be friendly with humans.” Yes, it is through understanding that humans and nature come together.

In distinguishing knowing from understanding, Charlie Russell hints at the persistence of the man versus nature dualism that has been so pernicious to both sides of the equation. The philosophical writings of Bacon and Descartes “drained [nature] of her inner life, rendered a deaf and blind apparatus of indifferent and value-free law,” so, no longer the domain of God, it could be mastered by man. And it was and continues to be. The epistemological legacy of Newtonian physics in which the world is a “mosaic of bits and pieces that interact through mechanical laws” remains with us today. Disconnection, fragmentation, and separation stemming from Newton’s equations inform our way of perceiving nature, even though, ironically, they are antithetical to the seamlessness of nature.

Certainly, such a separation helped make economic and technological progress possible, but it came at the cost of impoverishing both humanity and nature. Seeing the world through disconnection and difference “has generated the endless cycles of ethnic strife, war against wildlife and environmental collapse gripping the planet today.” It also ravaged the human psyche. The psychotherapist and mental health advocate, James Barnes, argues, in his article in Aeon, the psychological costs of the trade-off:

“In the previous episteme, before the bifurcation of mind and nature (…) we had a ground, guide and container for our ‘irrationality’, but these crucial psychic presences vanished along with the withdrawal of nature’s inner life and the move to ‘identity and difference’. In the face of an indifferent and unresponsive world that neglects to render our experience meaningful outside of our own minds – for nature-as-mechanism is powerless to do this – our minds have been left fixated on empty representations of a world that was once its source and being. All we have, if we are lucky to have them, are therapists and parents who try to take on what is, in reality, and given the magnitude of the loss, an impossible task.”

This is the world we live in. Communion with nature became the exploitation of nature, as understanding, an attribute of love, gave way to knowing, an attribute of mastery. Not a trivial difference. Understanding, just as love, requires subjectivity as well as the interdependence between an object and an observer. They become inseparable from each other in a mutual dance of trust, respect, and tenderness. In contrast, knowing, or collecting information, presupposes an emotional detachment and alludes to superiority and objectification. This is not what Charlie and Bradshaw are seeking.

Image Credit: Tom Ellison

Photo courtesy of Gay Bradshaw

How can we mend this broken world? Charlie’s story, as told by Bradshaw, shows us a way out. But, since the book’s message is so much closer to the profound teachings of Darwin, Thoreau, and Muir than to precepts of pop-psychology literature, there are no numbered steps to follow or life recipes to memorize. Charlie would have abhorred such avenues of “knowing”. Instead, understanding, listening, paying attention, immersing oneself in the wholeness of the experience, and emptying the mind of the persistent habits of thought and daily preoccupations – this is what is needed. It’s so simple and yet so difficult.

Few can live like Charlie Russell, but many can learn from Charlie Russell. And from Gay Bradshaw. Towards the end of the book, the disparate backgrounds of the author and her subject fully coalesce. Charlie’s way of perceiving the world finds validation in quantum physics, the realm of science in which Gay Bradshaw has vast experience and expertise. In Bradshaw’s words, referring to physicist David Bohm, quantum physics provides a strikingly different understanding of nature. In contrast to Newtonian fragmentation, it sees “wholeness and harmony” as an overarching principle.

We can’t tear ourselves apart, quantum physics proves. Separating from or stepping out of nature to evaluate it “from a rigid point of view” is impossible because we are part of nature. The answer lies in accepting our own nature and the reality of its inalienable connection to the all-encompassing natural world. Consequently, if we do that, if “humanity aligns its vision and behaviour to match the true quality of nature, what quantum phenomena reveal as wholeness and harmony, our species can move from cultures of conflict to those of collaborative wellness.”

Charlie’s intuitive insights coincide thus with findings of the seemingly esoteric science. His experiences from living a solitary life in the harsh Russian landscape and discoveries of modern physics point to the same message of wholeness. Again, of course, the clarity of this message contrasts with the challenge of living it, letting it pierce the armour we have chosen to wear. But the difficulty of this primordial “merger” does not lessen its necessity. In the end, succeeding at this task is the only way out for both humanity and nature which, in the age of the Anthropocene, increasingly depends on us. And success is an attainable goal. Our way of interacting with nature will change if we give both ourselves and nature a chance. If we try to live Charlie’s way.

Talking with Bears offers a lot to its readers, but Charlie and Bradshaw demand a lot from them, as well. Although explicitly, the book is about peacefully coexisting with Grizzly Bears, it is also a metaphor for the possibility of the relationship with nature based on inclusion, acceptance, harmony, and attentive presence. Such a relationship is within our reach; we should all strive for it. Once we have traversed even a part of the journey on this different path, a reward, elusive so far, awaits us. As Charlie said, “I’ve learnt that the greatest joy and sense of peace come from living with, not against, nature.”